Archive

Today We Toot Our Own Horn! First Team named No. 1 in California sales

|

|||

Costa Mesa-based First Team Real Estate ranked No. 1 in sales transactions in California and No. 8 in the U.S. in sales volume among the country’s top 300 real estate companies in 2010, according to RISMedia’s Power Broker Report. The family-owned, nonfranchised company has sold more homes in Orange County than any other real estate firm in the last decade and, despite the struggling housing market, has managed to increase its overall position. The firm has expanded beyond O.C., with property transactions in Beverly Hills, Marina del Rey, Pasadena, Westlake and San Diego. “Our continuous growth and ever-improving performance, particularly in one of the most challenging real estate markets in history, is a testament to our aggressive leadership and constant innovation that enables us to stay ahead of the market by anticipating and meeting the changing needs of consumers and agents,” said First Team Real Estate Founder and CEO Cameron Merage. Merage also credits the firm’s success to the brokerage’s “dedicated and well-trained agents and “sophisticated tools” that set high standards of value for the consumer. Established in 1976, First Team Real Estate has branched out to more than 60 locations and supports more than 2,000 employees and agents. Number 1 in California. Number 8 in the Nation.

|

|||

Forecast: Flat O.C. rents next two years

The Casden Real Estate Economics Forecast, from the folks at USC’s business school, predicts flat Orange County rents in the next two years – with occupancy rates barely changing.

That’s a bit of a contrast to industry and government reports showing rents slowing increasing in recent months as the local economy modestly improves.

Casden analysis:

- “Stabilized” employment picture from loss of 75,000 jobs in 2009 to gain of 6,500 jobs, in ’10. Unemployment rate in December 2010 was 8.9 percent, vs. 9.5 percent a year before. “Because of robust employment growth in preceding years, overall unemployment is still lower in Orange County than in neighboring metro areas such as San Diego, Los Angeles or the Inland Empire, and lower than the nation overall.”

- Demand for apartments increased in year ended Q4 2010 to net 5,830 units, up 39 percent over the prior four quarters. Two Orange County submarkets experienced negative net absorption for the year: Mission Viejo and Central County.

- Occupancy increased 1.2 percentage points in 2010, to 94.9 percent. Occupancy outpaced the West region by 0.8 percentage points, and had the second-best showing in Southern California.

- Average rents increased by 0.8 percent in 2010 to $1,475 at year’s end, while “same-store” rents remained unchanged. Orange County’s annual rent performance was the fourth-weakest among the 64 metro areas tracked nationwide by MPF Research.

- New Orange County apartment openings will drop precipitously in 2011.

- Orange County home prices, “remain high relative to the rest of Southern California. Both the employment picture and relative lack of home affordability have helped support the multifamily market in 2010.” Thank you, OCR

The Floating Dollar as a Threat to Property Rights

Seth Lipsky is the founding editor of the New York Sun. A graduate of Harvard College, he served in the U.S. Army in Vietnam as a combat correspondent for Pacific Stars and Stripes. A former senior editor and member of the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal, he has also served as editorial page editor of The Wall Street Journal/Europe, managing editor of The Asian Wall Street Journal, and assistant editor of Far Eastern Economic Review. In 2009, he published The Citizen’s Constitution: An Annotated Guide.

The following is adapted from a speech delivered on February 16, 2011, at a Hillsdale College National Leadership Seminar in Phoenix, Arizona.

TO BEGIN, consider one of the most important measures of property, the kilogram. It’s a measure of mass or, for non-scientific purposes, weight. According to the papers last week, a global scramble is under way to define this most basic unit after it was discovered that the standard kilogram—a cylinder of platinum and iridium that is maintained by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures—has been losing mass.

You may think that this is impossible. Of all the elements, iridium is the most resistant to corrosion, and the cylinder is kept in a facility at Sevres, France, where it is under three glass domes accessible by three separate keys. The cylinder itself is more than 130 years old and is what the New York Times calls the “only remaining international standard in the metric system that is still a man-made object.” The new urgency to redefine the kilogram comes from the fact that its changing mass “defeats,” as the Times put it, “its only purpose: constancy.”

The question I invite you to consider for a moment is what would happen if we just let the kilogram float? This is a question that was posed in an editorial last week in theNew York Sun. After all, the editorial said, we let the dollar float. The creation of dollars, and the status of the dollar as legal tender, is a matter of fiat. Its value is adjusted by the mandarins at the Federal Reserve, depending on variables they only sometimes share with the rest of the world. This would have floored the Framers of our Constitution, who granted Congress the power to coin money and regulate its value in the same sentence in which they gave it the power to fix the standard of weights and measures—like, say, the aforementioned kilogram.

Now, the record is clear in respect of how America’s founders viewed money. Many of them went into the Second United States Congress, where they established the value of the dollar at 371 ¼ grains of pure silver. The law through which they did that, the Coinage Act of 1792, noted that the amount of silver they were regulating for the dollar was the same as in a coin then in widespread use, known as the Spanish milled dollar. The law said a dollar could also be the free-market equivalent in gold. The Founders did not expect the value of the dollar to be changed any more than the persons who locked away that kilogram of platinum and iridium expected the cylinder to start losing mass. In fact, in this same 1792 law, they established the death penalty for debasing the dollar.

Today, members of the Federal Reserve Board don’t worry about how many grains of silver or gold are behind the dollar. They couldn’t care less. And this is what I believe is the most worrisome threat to property rights today. When the value of a dollar plunges at a dizzying rate—at one point in recent months it collapsed to less than 1/1,400 of an ounce of gold—Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke goes up to Capitol Hill and declares merely that he is “puzzled.” No “new urgency” to redefine the dollar for him. The fact is that we’ve long since ceased to define the dollar, and it can float not only against other currencies but even against 371 ¼ grains of pure silver.

So, the New York Sun asked, why not float the kilogram? After all, when you go into the grocery to buy a pound of hamburger, why should you worry about how much hamburger you get—so long as it’s a pound’s worth? A pound is supposed to be .45359237 of a kilogram. But if Congress can permit Mr. Bernanke to use his judgment in deciding what a dollar is worth, why shouldn’t he—or some other Ph.D. from M.I.T.—be able to decide from day to day what a kilogram is worth?

No doubt some will cavil that the fact that the dollar floats makes it all the more reason for the kilogram to be constant. But what’s so special about the kilogram? If the fiat dollar floats, one has no idea what it will be worth when it comes time to spend it. If the kilogram also floats, it will simply be twice as hard to figure out what something we’re buying will be worth. So what if, when we unwrap our hamburger, the missus has to throw a little more sawdust in the meatloaf?

Or let us consider a compromise. Let’s go to a fiat kilogram—that is, permit the kilogram to float—but apply the new urgency to fixing the dollar at a specified number of grains of gold. To those who say it would be ridiculous to fix the dollar but let the butcher hand you whatever amount of hamburger he wants when you ask for a kilogram, I say, what’s the difference as to whether it’s the measure of money or of weight that floats?

For that matter, one could go all the way and fix the value of both the kilogram and the dollar but float the value of time. You say you want to be paid $100 an hour. That’s fine by your boss. But he—or Chairman Bernanke—gets to decide how many minutes in the hour. Or how long the minute is. You know you’ll get a kilogram of meat for the price a kilogram of meat costs. But you won’t know how long you have to work to earn the money.

There was obviously a satirical element to that Sun editorial. But it’s not satirical to say that we are in a dangerous situation in our country in respect of the dollar, and that property rights are very much bound up in the question of money. After all, consider that kilogram. It is a cylinder. And it’s a cylinder the size of, say, a golf ball. The amount of mass that it is believed to have lost is measured in a few atoms, and yet the institution where they maintain standards is in a complete tizzy about it. The implications are said to be enormous.

The dollar, by contrast, has collapsed from 1/35 of an ounce of gold to less than 1/1,300 of an ounce of gold. If the kilogram had collapsed on that order of magnitude, there would be left only a small shard of that handsome grayish cylinder under the three glass domes at Sevres, France.

I understand that this is not where the property rights discussion is usually focused. It usually centers around the takings clause of the Constitution—the clause at the center of the landmark case that erupted when condemnation proceedings were launched against the homes in New London, Connecticut, of a woman named Susette Kelo and her neighbors. Under the Fifth Amendment, the government is prohibited from taking private property for public use without just compensation. That is a bedrock principle of American constitutionalism. What was special about Susette Kelo is that her property was taken for private use. It was coveted by a private, non-profit development corporation for private, for-profit use near a big pharmaceutical development that the town reckoned would benefit the public.

Mrs. Kelo and her neighbors went all the way to the Supreme Court to try to keep their homes. She lost the case, Kelo v. New London, albeit by a five to four vote. On the one hand, it was a terrible defeat for the principle of property rights. On the other hand, the decision was so alarming that states have begun changing their own laws to strengthen protections against the kind of raid on private property that Mrs. Kelo suffered. At least 43 states have already passed such laws. Rarely has the loser in a Supreme Court case established so great a legacy as Mrs. Kelo, whose case is one of the most important warnings we have had in my generation of the vigilance that is going to be required in respect of the right to property enshrined in the Fifth Amendment.

Which brings me to the question of how the law can be used to illuminate the problem of the floating dollar. What I consider the most astonishing legal question in the country came into the news in 2008, when Judith Kaye, the chief judge of the highest court in the state of New York, the Court of Appeals, filed a lawsuit in an inferior court, asking it to order the state legislature and the governor to give her a raise.

My first reaction, and that of my colleagues at the Sun, was to consider this something of a joke. Yet the more we began to look at the case, the more it threw into sharp relief the issue of the right to the property that comes to us in the form of a salary or is held by us in the form of savings. The judges on New York’s Court of Appeals, after all, hadn’t had a raise in more than a decade, and they were having an ever harder time making their salaries cover rising costs. In that they are just like the rest of us.

But it turns out that under the Constitution, judges are not quite like the rest of us—and in a way that lies at the heart of the American Revolution. Indeed, in the Declaration of Independence, one of the reasons our Founders listed for breaking with England was that King George III had “made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.” So they wrote into the Constitution not only that judges would have life tenure (with good behavior), but also that the pay of a judge would not be diminished during his term in office. This principle that one can never lower the pay of a judge is also in many state constitutions.

So if in, say, the year 2000 a judge was paid in dollars that were worth 1/265 of an ounce of gold, and if today that same judge is being paid with dollars worth less than 1/1,300 of an ounce of gold, has the judge’s pay been diminished?

The more I’ve thought about it, the more I have been nagged by the thought that judges’ pay could be the device with which to attack the legal tender law I have come to regard as the greatest threat to property in America. This is the law establishing that paper money in America must be accepted in payment of debts, public and private. The Founders themselves hated paper money. Washington, whose picture is on the one dollar bill, warned that paper money would inevitably “ruin commerce, oppress the honest, and open the door to every species of fraud and injustice”; Jefferson, whose picture is on the two dollar bill, called its abuses inevitable; as did Madison, whose picture is on the $5,000 bill. Paper money, he said, was “unconstitutional, for it affects the rights of property as much as taking away equal value in land.”

I’m not so sure that the existence of paper money is the problem. The problem is the requirement that a one dollar paper note be accepted in lieu of 371 ¼ grains of silver. Certainly when the greenback was introduced—as it was by President Lincoln—it was for a cause, the Union, that was worth enormous risks. The Treasury Secretary who helped him put through the greenback as a war measure, Salmon Chase, became, in 1864, the sixth Chief Justice of the United States; and when the concept of legal tender finally came up for consideration, Chase ruled against the greenback. President Grant, however, eventually got two new justices on the court, and legal tender was established in a series of rulings—one involving the purchase of some sheep, the other of some bales of cotton, and another some land—known as the Legal Tender Cases.

A few months ago, I called Bernard Nussbaum, who was representing Judge Kaye, and asked him why she didn’t challenge legal tender head on. He told me he feared the Legal Tender Cases couldn’t be overturned. It was too heavy a lift. So instead he fought the case on separation of powers grounds. It seems that the New York legislature had said it would not give the judges of New York a raise until the legislators got a raise. The judges sprang on this as a transgression of separation of powers—and, no surprise, when they heard their own case, they ruled against the legislature. A few weeks ago, the legislature decided to delegate to an independent commission the job of deciding judges’ pay.

By my lights, this delegation to an unelected body, even if the legislature could overrule it, was an unsatisfactory outcome. But it turns out that the judges of New York are not the only jurists who are furious about the diminishment of their pay. A group of federal judges is also in court, fighting over their salaries. In the case of the federal judges, Congress had some time ago enacted a law that gave them an automatic pay increase designed to keep up with the Consumer Price Index. But then, as deficits got out of control and Congress’s own salary lagged, Congress suspended the automatic pay increase.

At that point, a coalition of federal judges went into court. Their aim is limited: to force Congress to reinstate the automatic pay adjustment. To understand the scale of what one is talking about, consider the pay of but one of the plaintiffs, Judge Silberman. I don’t know his exact salary. But at the time he was assigned to the District of Columbia Circuit of the United States Court of Appeals, the salary of a federal appeals judge—$83,200—was worth 258 ounces of gold. Since then, the value of the pay of a judge of one of the Appeals circuits—$184,500—has been diminished to 139 ounces of gold.

At this very hour, the judges’ petition in their pay case is before the United States Supreme Court. And while I believe the justices have been wronged by Congress, I hope they lose on the question of whether a suspension in the automatic pay adjustment is unconstitutional. That should get them angry enough to come back and look legal tender in the face. They could force Congress to pay them in the gold or silver equivalent of a federal judge’s salary at the time they were appointed to the bench. It would move judges closer to the kinds of salaries the lawyers before them are receiving.

And people would start to ask: If judges deserve honest money, why shouldn’t the rest of us?

To those who suggest that such a scenario is far-fetched, one can say, no more far-fetched than the notion that the post-Civil War monetary system could be erected on Supreme Court decisions in a pair of disputes over payment for a flock of sheep and some bales of cotton. Or that centuries of law on abortion could be overturned in a fell swoop by a Supreme Court ruling in the case of a woman who later changed her mind. Could the court cast aside precedent to decide such a sweeping issue as legal tender? It certainly didn’t hesitate—nor should it have—in demolishing the notion that racially separate schools could be equal. With everyone from the United Nations to Communist China today calling for the abandonment of the dollar as a reserve currency, is it so hard to imagine that the Supreme Court might revisit the Legal Tender Cases?

It may be that the judges will lose their pay case, just as Susette Kelo lost her house, or that they will win a partial victory and the Supreme Court will shy away from confronting legal tender. But we know from Mrs. Kelo’s case that this needn’t be the end of things. People began to see the logic and think about property rights, and now at least 43 states have passed laws to make it harder for state and local jurisdictions to use the power of eminent domain to seize private land for someone else’s private use.

Could such a thing happen with money? Well, there is a part of the Constitution called Article I, Section 10. It is the section that lists the things that states can never do. And one of these prohibited activities is making legal tender out of something other than gold or silver coin. So what is happening now is that a growing number of states, watching the sickening plunge in the value of federal money, are starting to explore how they can set up monetary systems based on gold or silver coins. The most recent effort was launched in Virginia, where there is a bill before the General Assembly to set up a joint committee to study the question. There have been early stirrings—just stirrings—in the legislatures of several other states.

Could the entry of the states into the monetary role be a reaction to a failure at the federal level, the way the states reacted to the failure of the Supreme Court to enforce Susette Kelo’s Fifth Amendment rights? It would be inaccurate to make too much of these efforts. But it would be shortsighted to make too little of them. Strange things can happen. It is even possible that one can take a cylinder of platinum and iridium, lock it away in a room under three glass domes, secure it with three separate keys, and come back in a few years to discover that part of it has disappeared. And the New York Times will write an editorial about the value of constancy.

Reprinted by permission from Imprimis, a publication of Hillsdale College

Dave & David Warner

Flyfishing – Depuy Springs, Montana

Weekly Mortgage Rates 2/17/2011

| February 17, 2011 | 30-Yr FRM | 15-Yr FRM | 5/1-Yr ARM | 1-Yr ARM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Rates | 5.00 % | 4.27 % | 3.87 % | 3.39 % |

| Fees & Points | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Margin | N/A | N/A | 2.75 | 2.76 |

From Freddie Mac

Dave & David Warner

Fishing Hole Snow is Finally Melting.

We can see the deer now – spring must be on it’s way.

Thank you, Hans

Dave & David Warner

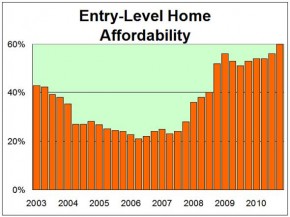

O.C. home affordability triples

The percentage of households able to afford an Orange County starter home has tripled since the housing market peaked, the California Association of Realtors reported.

By the Realtors’ math, 60% of Orange County households could afford to buy the typical “entry-level” house in Orange County in the fourth quarter of 2010.

By comparison, just 21% could afford that house in the spring of 2006, the low point for housing affordability in O.C.

Last quarter’s level was also the highest level of home affordability in Orange County in figures dating back to 2003.

Using the Realtors’ methodology, a household would need to earn about $63,000 a year to afford the typical “entry-level” house in Orange County.

That’s down from around $118,000 in the spring of 2006.

That’s based on an entry-level home price of just under $409,000, with monthly house payments at $2,100.

The Realtors’ affordability index measures the percentage of local households able to afford a starter home — valued at 85% of the area’s median house price. The index assumes that buyers are making a 10% down payment and getting an adjustable-rate loan. The association considers its measure “the most-fundamental measure of housing well-being for first-time buyers.”

The Realtors’ report comes a day after the Wall Street Journal reported that housing affordability returned to pre-bubble levels in a growing number of U.S. markets over the past year.

According to Moody’s Analytics, the U.S. ratio of home prices to annual household income reached a peak of 2.3 in late 2005, but had fallen to 1.6 by September, matching the lowest level in the 35 years, the WSJ reported.

While the Realtor index is only a rough estimate of how many residents can actually afford starter homes, it does track the overall trend caused by falling prices and lower interest rates.

In addition, rising interest rates in recent weeks likely have reduced the current number of households able to afford a home. The average interest rate of 30-year home loan rose above 5% in the past week, according to Freddie Mac’s weekly survey.

Statewide, the report shows:

- 69% of California housesholds could afford the entry-level house in the fourth quarter, matching the record-high set in the first quarter of 2009.

- 75% of California households could afford the entry-level condo.

- That compares to a national affordability rate of 80%.

- The minimum annual income needed to afford the California starter home (costing just over $256,000) was $39,600.

- Affordability either matched or set record highs in all regions of the state last quarter.

- Affordability in the state last quarter ranged from a low of 42% in San Francisco to a high of 86% in Merced County.

Thank you, Jeff Collins, OC Register

Dave & David Warner

Just Listed – Lease in Fullerton

Spectacular Views...Disneyland Fireworks, city lights, Walk to all schools and all colleges and beautiful downtown Fullerton. A beautiful 5 bedroom home. One bedroom is a small suite off the front entrance. Great yard for kids and pets.

Click on the Link below or all the information on this property.

http://www.postlets.com/rentals/mini_385.php?pid=5079793

Dave & David Warner